Today is Palm Sunday, the beginning of Holy Week.

Maybe you’re like me and grew up with the Sunday School version of Palm Sunday.

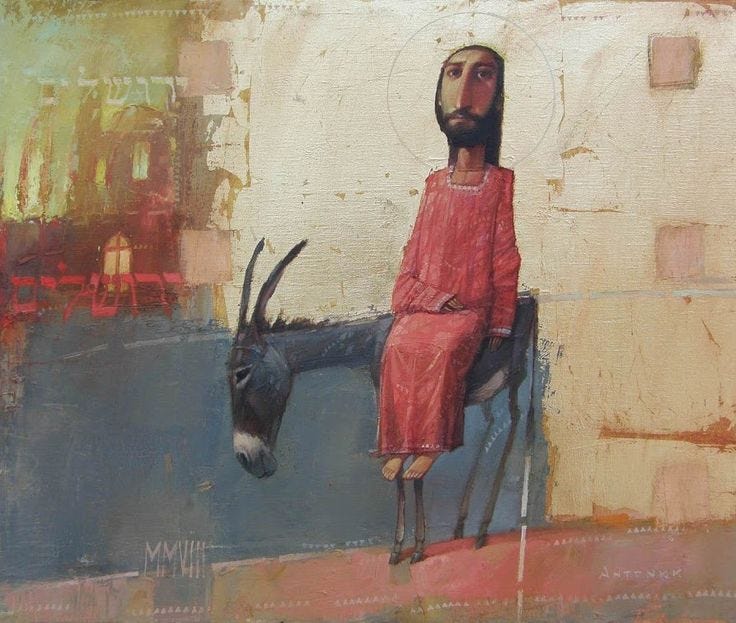

You might have flashbacks to palm fronds, a donkey, and yelling “HOSANNA” as loud as you could — to be sure, these are elements of the story. But the meaning—or let’s say shock value—of this story is lost on us.

Palm Sunday is full of political tension, questions of power, and the nature of the Kingdom of God. We need to re-gain the shock of this story for our American situation that confront the idolatrous “fascist-lite” elements swirling in our social world and, by consequence, our churches.

If you need a glimpse of this shock value and what it offers, just look at the name, Palm Sunday. New Testament scholar Esau McCaulley points out only one gospel (John) mentions how the crowds used “palms” to welcome Jesus in his pilgrimage ascent to Jerusalem—and (crucially) it wasn’t Jesus’ idea.

Palms had a specific meaning for the crowd of pilgrims welcoming Jesus, one pulled from Israel’s recent past. They were a symbol of nationalist zeal. In 165 BC, a generation earlier, they were used to celebrate the Jewish Maccabean revolts against the Seleucid Empire.“Those plants” writes McCaulley, “were symbolically linked to military victories and Messiahship.” On Palm Sunday, people reached for “palms”— symbols of revolutionary violence—much like many reach for a Betsy Ross flag on the Fourth of July.

This is just one particular example.

From AD 30 to AD 2024

In a recent speech, Donald Trump told a group of Christian Broadcasters at the National Radio Broadcasting that those who have been charged for involvement on January 6 are “persecuted Christians.”

Over the last three years, the most common pushback to my dissertation on January 6 was that it had nothing to do with “true” Christians—a convenient No-True-Scotsman.

But now, the mythos of January 6 draws on these rogue theological elements. It has become an organizing feature of Trump’s campaign. In the speech, he promised to “bring Christianity back” (but, where did it go?) and suggested the way to do that was by taking the path of “redemptive” violence:

“Christians, they can’t afford to sit on the sidelines in this fight. They have to really get out there. They have to do what they have to do, and they have to win. The chains are already tightening around all of us.”

The political choices given to as the “Christian” choice betray the gospel of the church’s witness. Trump positions himself as Christianity’s benefactor while wielding faith as propaganda in the pursuit of power. Those of us asking what it is to be responsible and to have faith in our present American situation should really sit with the Triumphal Entry afresh.

The triumphal entry—along with all of Holy Week— presents us with a decisive choice whether or not to follow Jesus as the Crucified One, a very narrow way. I’m so convinced of this that I made use of several key elements of the Triumphal Entry to frame my dissertation on January 6 and the rogue theological elements that charged it. This is proving to be—I think—the right decision. So let’s look at some of these dynamics that charge the story of the triumphal entry.

Under The Foot of Rome

Jesus’ life stands between two periods of revolutionary violence in Judea. When Caesar Augustus annexed Judea to the Roman Empire in A.D. 6, ordering a census, he triggered a small Jewish revolt led by a Galilean, Judas of Gamala. Some 30 years after Jesus’ death, in A.D. 66, another revolt happened—this time much larger. It was called the First Jewish-Roman War that ultimately resulted in the siege of Jerusalem and destruction of the Temple in A.D. 70.

The gospels are not ignorant of these social worlds and struggles. In fact, the struggle with Empire, particularly Rome, pervades Jesus’ ministry. Roman occupation was a matter of daily existence, and survival. It shows up in Jesus’ moral teaching to “go a second mile” that acknowledges the common practice of a Roman soldier enlisting a Jewish person to carry their pack. It was understood a Roman could detain a Jew for this service up to a mile. Jesus’ offers a path of freedom that would lead to a human encounter between the oppressed and oppressor. By going an extra mile, Jesus combines a vision of resistance, freedom, and witness in the Kingdom of God. By going an additional mile, the oppressed shows their freedom in a way that provoke the Roman solider into re-considering the person in front of him—similar to the famous protest phrase of the Civil Rights Movement: “I Am A Man!”

Failing to understand this social world of Jesus—one that burned with insurrectionary zeal against Rome, one longing for a Messianic deliverance—will absolutely impact our readings of the gospel’s witness. These struggles come to a climax in Holy Week, beginning with Jesus’ dramatic entry into Jerusalem.

Passover Week: A Security Threat

Jesus arrives in Jerusalem to observe Passover or Pesach—which marks the liberation of Israel from Egypt. It is a defining story in Israel’s heritage, of the defeat of Pharaoh, and freedom from oppression and slavery. Now, Israel found itself under the foot of Rome. The Passover narrative itself stirred up resentment against the Roman occupiers.

The Passover narrative reminded Israel of the defeat of Empire. But then there was the gathering of Israel at Jerusalem to celebrate it. During Passover, hundreds of thousands of pilgrims from the diaspora—spread across the Hellenized world—would converge on Jerusalem.

If we were looking at this situation from the position of the Roman Empire, we might call it a “security threat.”We’re familiar with this in our own films and myths. It was given the fictional treatment in the Star Wars series, Andor—where an Imperial outpost, full of white-armored Stormtroopers was overrun by Rebels who used a local religious festival as cover for their assault on the base. That is exactly the sort of threat Rome was primed to resist and put down.

And so—each Passover week—the occupying Roman governor would travel from Caesarea Maritima, a coastal city on the Mediterranean, and bring a contingent of Roman troops to reinforce the garrison at Jerusalem.

Rival Processions

We talk a lot about Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem. But readers of the gospels, especially Mark’s gospel—written during the Jewish revolt of A.D. 66—would have been well aware of another notable arrival: the Roman governor.

Yes: Pilate had a triumphal procession. And in fact, the whole idea of a “triumph” was a Roman invention. Originally reserved for victorious military leaders, then eventually associated with divinizing Caesar, the “triumph” was a parade of Roman ideology and a projection of power.

Pilate rehearsed his own form of “triumph” as he entered Jerusalem on Palm Sunday before the Passover week began. His arrival, meant to reflect Caesar’s power—the ruler he represented, and would have come with displays of military power: Roman banners, war horses, and soldiers—leaving the pilgrims no doubt who claimed to be in charge, and a clear threat to those who would dare test such power.

The fact the Roman governor arrived in force before Passover restores the shock value of Jesus’ own “triumphal entry.” Not only was Jesus intentionally staging a counter-procession, on the opposite side of the city to Pilate, but he was doing so in ways that rehearsed and reframed Israel’s history. His choice of a donkey wasn’t just in contrast to Pilate’s war horse, it wasn’t just a symbol of Maccabean revolts a generation earlier, it was a reference to Zechariah 9:9…

“Rejoice, rejoice, daughter of Zion shout aloud, daughter of Jerusalem; for see, your king is coming to you; his cause won, his victory gained, humble and mounted on an ass…”

The triumphal entry was both a dramatic rehearsal of Israel’s hopes and a direct challenge to Imperial claims to power. Both converged in Jesus, in the Kingdom he was set to unveil and secure, not from a throne but from a Cross. The triumphal entry of Jesus was a counter-protest to the way of Empire.

The Way of the Cross

In the triumphal entry of Jesus we find explicit opposition to both Roman imperialism and insurrectionary, diasporic nationalism—and this is a common tension and struggle in many of the social worlds that shaped Christian witness in the New Testament. Dr. Willie Jennings writes,

Faith is always caught between diaspora and empire. It is always caught between those on the one side focused on survival and fixated on securing a future for their people and on the other side those intoxicated with the power and possibilities of empire and of building a world ordered by its financial, social, and political logics that claim to be the best possible way to bring stability and lasting peace.

This Palm Sunday, with an eye on the story of Jesus and our own situation in America, we find a fresh path of faith and responsibility on the way of Jesus. Faith discovers the liberating way of the Kingdom, which is, ultimately, the way of the Cross.

Faith defies those who, as Philip Ziegler said this week in his Princeton lectures on Satan, tempt us to take the way of “diabolical unlearning,” to choose other means to accomplish God’s ends. Jacques Ellul captured this when he wrote, “Satan offers all the kingdoms of the world, Jesus rejects but the church accepts.”

The church cannot take up the sword or the logics of Empire to defend its interests. It’s equally strange, a failure to recognize its place in American society, for white Christians to understand ourselves as a persecuted, diasporic minority. We took quickly call ourselves “persecuted” — failing to realize that the persecution which most afflicts white Christians in America is not the oppressive foot of Empire but the soft persecution of privilege and power.

Trump is a persecutor of the church, a rival procession to the way of Jesus. He is the latest in a long line of aspiring Caesars, promising protection and power to the church that amounts to little more than persecution. As Hilary of Poitiers wrote of the Emperor in the 4th century:

“He does not stab us in the back but fills our stomachs, does not seize our property to lead us to life but stuffs our pockets to lead us to death, does not free us by putting us in prison but enslaves us by attendance at court, does not lash our bodies but steals our hearts, dow not behead us with swords but kills the spirit with gold, does not publicly threaten us with the take but privately kindles the fires of hell. He does not fight to avoid defeat but flatters in order to dominate He confesses Christ to deny him, seeks uniformity to banish peace, compromises with heretics to be rid of Christians, honors priests to abolish bishops, builds churches to destroy the faith…”

We the church are not fated, but holy. That is, we are not set into an unworkable situation. We are not forced into Trump’s procession. We are set apart, as ekklesia “called out” precisely in this present situation as responsible witnesses to the power of God. We are not caught between two bad choices, either the logic of Empire or insurrection.

We might ask ourselves today: what triumphal procession are we joining?

More Reading:

“Jesus, as security risk: Insurgency in First Century Palestine?” by Rose Mary Shelton

“Jesus’ Entry Into Jerusalem” by Juho Sankamo

“Jesus’ Royal Entry Into Jerusalem” by Brent Kinman

“The Last Week of Jesus” by Marcus J. Borg and John Dominic Crossan